The presidential election is a fairly muted, low-key affair in India, largely owing to the fact that the President is little more than a ceremonial figure. However, in a charged political atmosphere even something ceremonial like a presidential election can turn out to be a slug fest- a term which best describes the drama that unfolded after the death of president Dr. Zakir Hussain in 1969.

Few could have imagined it then, but the events of 1969 would have a profound impact on the political landscape of India for several decades to follow. In this article, we shall recount the drama that precipitated the crisis.

Prelude: An Uneasy Truce

As we saw earlier, the electoral debacle of 1967 led to a truce between Indira Gandhi and Morarji Desai, brokered by the syndicate. If the parties backed off before push came to shove, it was purely owing to the fact that it was a question of survival.

It wasn’t long before the differences started showing. Morarji Desai’s cohorts stepped up the frequency of their attacks on the prime minister. The syndicate- firmly on Morarji’s side after the currency devaluation– made no secret about its desire to get rid of her. Wise enough to sense that the tide was in her favour, if not the time, Indira Gandhi opted to wait for the right opportunity before striking.

Both sides were out to destroy the other. It only remained to be seen who would fire the first shot.

First Strike

President Zakir Hussain died in office on 3rd May 1969, less than two years after Prime Minister Indira Gandhi had prevailed over the syndicate to have him elevated. Dr. Zakir Hussian’s untimely death gave the party bosses a fresh opening, one they were bound to exploit.

Kamaraj made a proposal to Indira Gandhi to nominate her for the presidential race. As anyone familiar with Indian politics would know, elevation to the presidency is but a polite way of pensioning off. Naturally, Mrs. Gandhi politely turned down the proposal. And so the Congress Parliamentary Board was scheduled to meet on Friday, 11th July to discuss the vexed issue.

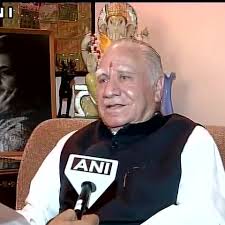

Behind the scenes, the Syndicate decided that Neelam Sanjiva Reddy, then Lok Sabha Speaker and fellow syndicate member would be the party’s presidential candidate. Given the stranglehold they had on the party organisation, the election of the Syndicate’s chosen candidate would be a formality. The die, it would seem, was cast.

But the drama had only just begun.

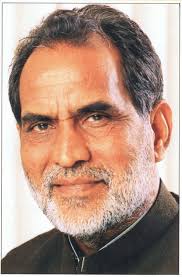

Neelam Sanjiva Reddy (1913-1996)

Counter-Strike

Indira Gandhi, who had already come a long way since her tentative beginning in 1966 circulated a note on “stray thoughts” to the Congress Working Committee, outlining her vision. The note proposed, among other things, bank nationalisation, land reforms and curbs on industrial monopolies. In short, Mrs. Gandhi was proposing a further leftward shift.

The ploy successfully drove a wedge, since there was little ideological unanimity within the Syndicate. However, Home Minister Y.B. Chavan successfully brokered a truce, securing a unanimous resolution calling on the central and state governments to implement the Prime Minister’s proposals.

With a keen eye on the forthcoming national elections in 1972, Indira Gandhi had secured the necessary support for implementing her economic vision. However, the presidential question remained unresolved.

The Plot Thickens

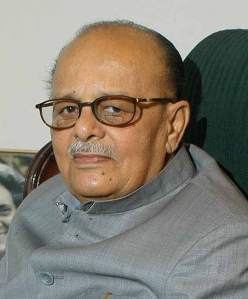

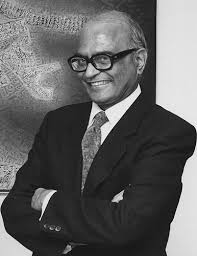

The logical choice for president was acting president V.V. Giri who, having been the Vice President, was first in line. He was Prime Minister Indira Gandhi’s first choice too. However, with the party bosses plonking for Reddy, she attempted to get around the situation by proposing the candidature of Food & Agriculture Minister Jagjivan Ram, supported in this quest by senior Congressman Fakhruddin Ali Ahmed. In the event, she was outvoted.

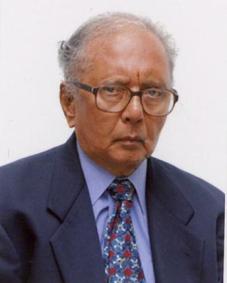

V V Giri (1894-1980)

A fresh twist occured at this stage, as V.V. Giri- who was understandably furious at being overlooked for a position over which he had the most legitimate claim- resigned as acting president and filed his nomination in the capacity of an independent candidate. He instantly won support from most opposition parties.

Indira Strikes Again

V.V. Giri’s revolt presented Indira Gandhi with a God sent opportunity. However, she needed to consolidate her own position within the party before she could throw in her lot with Giri. Having already won support for her economic vision, she decided to proceed with the nationalisation of banks. Fortunately for her, Morarji Desai- Deputy Prime Minister and Minister of Finance- unwittingly played into her hands by opposing the proposals.

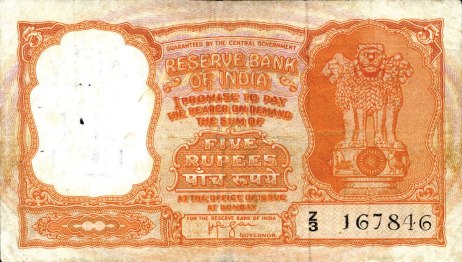

Sensing the opportunity to kill two birds with one arrow, Mrs. Gandhi announced the decision to nationalise 14 banks on 29th July 1969. Immediately thereafter, she relieved Desai of the finance portfolio and took charge herself, ostensibly for the purpose of gaining experience of running that ministry.

That effectively left the veteran Desai as Deputy Prime Minister without a portfolio. Gandhi told him that he could continue with a different portfolio. Predictably, Desai conveyed his inability to do so- which is precisely what the Prime Minister wanted anyway. For good effect, Gandhi described the decision as

…the beginning of a bitter struggle between the common man and vested interests in the country

Since the banking sector was dominated by a handful of business families, Mrs. Gandhi had effectively portrayed herself as a crusader in the struggle against vested interests, setting the theme for the next national elections due in 1972.

Another card up the sleeve

With the Syndicate divided over the issue of nationalisation of banks, Indira Gandhi played yet another masterstroke when it came to the presidential vote.

The Congress held over 52% of the total votes in the electoral college that was to elect the President. It effectively meant that the party’s candidate was an assured winner. It was being whispered that the candidate, Sanjiva Reddy, would use his powers- once elected- against the Prime Minister. His election was a mere formality now, or so it seemed to him and fellow syndicate members.

Fakhruddin Ali Ahmed (1905-1977)

To ensure that no stone was left unturned, party president and Syndicate member Nijalingappa issued a whip instructing all Congress members of parliament to vote for Reddy. Indira Gandhi, true to nature, kept all cards close to her chest until the eleventh hour. On the night of 15th August, with the presidential vote just hours away, she called upon party members to vote according to their conscience.

In effect, she had called upon the party to choose between her and the syndicate. Both sides now waited with bated breath.

The Presidential Vote

On Saturday, 16th August 1969, the electoral college went to vote to choose which of the 15 candidates would become the fourth President of India. With the Congress vote split, neither Reddy nor Giri achieved the necessary numbers and the third major candidate C.D. Deshmukh (the opposition’s nominee) emerged a distant third.

Consequently, by virtue of the provisions of Presidential and Vice-Presidential Election Rules, 1952 the deadlock had to be broken by taking into account the second preference given in the Deshmukh Ballots (electors have to indicate their preference by marking candidates in numerical order of preference). A review of the Deshmukh ballots gave independent candidate V.V. Giri a narrow win.

Mrs. Gandhi had won the battle. The war was not yet over.

Jagjivan Ram (1908-1986)

Aftermath

- V.V. Giri served as fourth president of India, earning the image of “Rubber Stamp” president due to his unquestioning support to Prime Minister Indira Gandhi. Honoured with “Bharat Ratna” after his retirement, he passed away in 1980.

- The person who supported Indira Gandhi in her ‘presidential’ struggle against the Syndicate- Fakhruddin Ali Ahmed- would succeed V.V. Giri to the presidency in 1974. He is best remembered today for declaring the emergency at Mrs. Gandhi’s behest. He passed away in office in 1977…

- …when he was succeeded by Neelam Sanjiva Reddy, who finally achieved the distinction of being elected the President under the Prime Ministership (ironically) of Morarji Desai

- Indira Gandhi’s open declaration of war precipiated an intra-party crisis, resulting in a split in December 1969 which would leave the party completely under the control of Indira Gandhi and her family

- Jagjivan Ram, the Dalit leader whom Mrs. Gandhi attempted to pension off, would be instrumental in bringing down Indira Gandhi in the run up to the general election in 1977. His daughter Meira Kumar would serve as the first woman speaker of the Lok Sabha (2009-2014)

- Dr. Zakir Hussian’s son in law Khurshed Alam Khan would serve as Union Minister for External Affairs, as would his grandson Salman Khurshid

Sources

- Srinath Raghavan, Twists & turns of 1969 Presidential Race Still the Most Sensational, Times of India, 18th June 2010

- R.J. Venkateshwaran, Indira Gandhi versus Morarji Desai — The real reason for bank nationalisation, The Hindu Business Line, 7th February 2000

- Inder Malhotra, Rear View: Presidential tales, Indian Express, 30th July 2015

- Robert L. Hardgrave, Jr., The Congress in India — Crisis and Split, Asian Survey, Vol. 10, No. 3 (Mar., 1970), University of California Press