Tags

BJP, Congress, Economic Crisis, Liberalisation, Politics, Reforms

This is the first in a series of three articles on the reforms of 1991

On Thursday, 20th June 1991, Pamulaparti Venkata Pigalle Narasimha Rao sat down for a briefing on the state of the Indian economy. It is doubtful whether he would have imagined being there even in his wildest dreams as late as a month before. Not even a fiction writer could have scripted the chain of events that had led to the present.

There remained less than 24 hours to go before P.V. Narasimha Rao was to be sworn in as the ninth prime minister of India. Coming as it did at a time of economic difficulties, it was logical for the man who was to head the government to get first-hand knowledge about the state of the economy.

Having held multiple cabinet portfolios in the past, Rao knew better than most the extent of the rot, and yet nothing could have prepared for the shock he received as Cabinet Secretary Naresh Chandra briefed him about the current state of the economy. His reaction was

I didn’t know it was this bad

The events that unfolded over the month that followed would change the course of Indian history.

India in 1990-91

The Iraqi invasion of Kuwait in August 1990 resulted in a dramatic spike in the price of crude oil, which more than doubled from $17 per barrel in August to $36 per barrel in October. The price spike proved to be a short-term phenomenon. However, for a country like India which depended almost entirely on imports for its oil requirements, and one whose economy was already in a precarious condition, the spike was crippling.

The seeds for the disaster were sown in the 1970s, when the GDP grew at a measly 3.5%, even as the population increased nearly 25% to 683.3 Million by 1981. Attempts to stimulate growth during the 80s resulted in the GDP growing at over 5% during the decade. Unfortunately, the growth was unsustainable, fuelled as it was by government spending. By 1990 the government of India was paying Rs. 35.3 out of every Rs. 100 it was earning only to pay interest on its borrowings.

Prime Ministerial Musical Chairs

So dire was the situation, that the National Front government headed by then Prime Minister V.P. Singh borrowed $550 Million from the International Monetary Fund (IMF) in September 1990. Fearing a political backlash at a time when it was surviving on outside support, the government was forced to do so surreptitiously, without publicly disclosing it.

In the event, the cloak-and-dagger nature of the operation proved futile, as Singh’s government collapsed when ideological differences resulted in the BJP withdrawing support in November. Samajwadi Janata Party (SJP) leader Chandra Shekhar, a former Congressman himself, formed a new government with outside support from the Congress.

In the meanwhile, the balance of payments situations had deteriorated even further. In January 1991 the new government, with Yashwant Sinha as its finance minister, convinced the IMF to approve two loans- $775 Million under the first credit tranche and $1.02 Billion under the compensatory and contingency financing facility. In return, the government pledged to initiate economic reforms in the union budget to be presented in February.

V.P. Singh (1931-2008)

Chandra Shekhar’s cabinet, led by Finance Minister Yashwant Sinha drafted the proposed economic reforms, much to the discomfort of the Congress. Financial Times famously said that Rajiv Gandhi (former Prime Minister and the then leader of the Congress) was desperately trying to pull the rug under him because Chandra Shekhar was an “uncomfortably successful” prime minister.

The comments were not off the mark, as the events of 4th March would prove, when the Finance Minister was to table the budget before parliament. Yashwant Sinha found himself unable to go ahead with the plans due to Congress intransigence. Unwilling to countenance any further bullying by Congress, Chandra Shekhar resigned on 6th March.

The resultant parliamentary deadlock meant that elections to the Lok Sabha had to be held afresh. It also meant that the economic crisis, which had been brewing since September 1990, could only be resolved when the new government would come to power post-elections, which would only happen around the beginning of June, as voting was to take place in three phases starting 20th May.

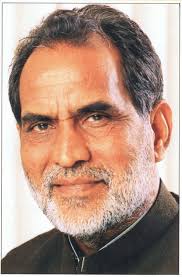

Chandra Shekhar (1927-2007)

Interim Measures

S.P. Shukla, the then Finance Secretary, did a sterling job of raising finances through a series of bridge loans to keep the coffers running. But those were just interim measures, analogous to keeping a patient on an artificial respirator. Desperate to preserve precious foreign exchange, the government was forced to cancel all import orders. Worse still, foreign suppliers had stopped accepting letters of credit (LCs) issued by Indian banks unless guaranteed or confirmed by internationally reputed banks.

So dire was the financial situation, that leaders across party lines- including Rajiv Gandhi (Congress), L.K. Advani (BJP), V.P. Singh (Janata Dal) and Chandra Shekhar (Samajwadi Janata Party)- concurred that the country had no other option but to seek a loan from the IMF. The new government that would assume office in the first week of June would have its work cut out.

A Searing Tragedy

At this stage came a tragic twist of fate. On 21st May the leader of the Congress and former Prime Minister Rajiv Gandhi was assassinated at Sriperumbudur near Chennai, where he had gone to address an election rally. Under the circumstances it was impossible to continue with a business as usual approach. The two remaining phases of voting were deferred to 12th and 15th June.

Rajiv Gandhi (1944-91)

The unexpected development meant the formation of the new government, which was expected to be completed by the first week of June, would not happen until the end of the month. By now India’s foreign exchange reserves had dipped below $1 Billion. The IMF and the World Bank had both pledged their support to India, but it was evident that no further financial assistance was forthcoming until economic reforms- a precondition to the assistance given in 1990- were initiated. Without the foreign exchange to buy oil, the country would come grinding to a halt. India was on the verge of a sovereign default.

Selling the Family Silver

In October 1990, the United Front Government had realised that it held one additional card up its sleeve in the event of an emergency- confiscated gold lying in the custody of the RBI. In October 1990 the V.P. Singh government had issued an ordinance to revalue the gold at market price. Six months later, confronted by the prospect of a humiliating sovereign default, the caretaker government under Chandra Shekhar gave its approval to act.

And so during the last days of May, 20 tonnes of gold were dispatched to London in four consignments to the Bank of England, in exchange for which the IMF advanced a fresh loan of $240 Million. The operation was carried out by the State Bank of India under utmost secrecy. Only a week later, when an official announcement was made by Finance Minister Yashwant Sinha, did the country get to know about the sale of gold.

Yashwant Sinha

A Twist of Fate

In the meanwhile the Congress, still the biggest party in the political landscape and the one most likely to return to power after elections, was without a head. With too many claimants to power, the party decided to revert to the glue that held together its disunited ranks: the Gandhi family. The newly widowed Sonia Gandhi, who had not been involved in active politics until then and knew too little about her adopted country, was understandably unwilling to assume the mantle herself.

Nevertheless, Sonia Gandhi called on the 78 year old P.N. Haksar, a veteran who had once been Indira Gandhi’s principal secretary and one of her most trusted advisors. On his recommendation, Mrs. Gandhi approached Vice President Shankar Dayal Sharma, a veteran leader and one of the most respected party men. Sharma, nearly 73 years old and struggling with failing health, politely declined the offer.

With S.D. Sharma out of the reckoning, Mrs. Gandhi’s second choice was another veteran Congressman who had lately announced his retirement from politics: former Andhra Pradesh Chief Minister P.V. Narasimha Rao. Rao had taken no part in the elections and was in fact in the process of packing his belongings so that he could vacate his quarters in Lutyens’ Delhi and resettle to his house in Hyderabad.

S.D. Sharma (1918-99)

And so the 70 year old Rao, who was all set to retire into obscurity, who had not even been his party’s first choice to replace the unexpectedly deceased leader, was now confronted by the prospect of becoming the Prime Minister of India.

The offer was too good to refuse.

Victory

The assassination of Rajiv Gandhi resulted in a massive wave of sympathy in favour of the Congress. Having fared poorly in the constituencies which went to vote on 20th May, the party swept the post-assassination phase to emerge with 244 seats in the Lok Sabha- 28 short of an outright majority, but enough to form the government with outside support from the communist parties.

P.V. Narasimha Rao, who had not even contested elections, contested a bypoll in Nandyal (Andhra Pradesh), winning by a massive 5 lakh votes. On 21st June 1991, he and his cabinet were sworn in.

P.V. Narasimha Rao

The newly formed government had just enough foreign exchange reserves to pay for two weeks of imports. Confronting it were the challenges of a looming sovereign default and an economy that was in dire straits.

The proposals drafted by Yashwant Sinha and his team had to be implemented as soon as possible. There was absolutely no scope for any further delay. But the political instability of the previous 18 months meant that reforms were still a long way away, as no attempt had been made to forge a political consensus until then.

P.V. Narasimha Rao and his team faced a steep challenge.

Sources

- C. Rangarajan, 1991’s Golden Transaction, Indian Express, 28th March 2016

- Shankar Aiyar, P V Narasimha Rao: Accidental PM and Accidental Reforms, New Indian Express, 19th June 2016

- Inder Malhotra, How Narasimha Rao Became PM, Indian Express, 6th April 2015

- Shankar Aiyar, Accidental India: A History of the Nation’s Passage through Crisis and Change, Aleph Book Company (2012)

- A.K. Bhattacharya, Two Months That Changed India, Business Standard, 2nd July 2011

- P.R. Ramesh, PV Narasimha Rao: The Outsider Who Dared, Open Magazine, 4th March 2016

- Swaminathan S. Anklesaria Aiyar, Unsung Hero of the India Story, Economic Times, 26th June 2011

- S. Venkitaraman, Return of India’s Gold, Business Line, 16th November 2009

- R. Nagaraj, Growth Rate of India’s GDP, 1950-51 to 1987-88, Economic and Political Weekly, 30th June 1990

- The 2002-03 Union Budget