In the previous article we saw how events in the south led to the East India Company getting involved in Indian politics for the first time. In this article, we shall see how the Company got involved in political machinations in Bengal, leading to the historic battle at Plassey.

Bengal in the 1750s

As was the case with regional rulers across the country in 18th century India, the nawab of Bengal enjoyed absolute authority albeit under the nominal vassalage of the Mughal sultan in Delhi. In keeping with the general atmosphere of lawlessness owing to weak central authority, there were several palace intrigues with multiple claimants to the various thrones across the country.

As the 18th century reached the midway mark, the nawab of Bengal was a man called Alivardi Khan, a man of humble origins who had made his way to the throne with a combination of intrigue and bribery. It says something about the prevailing atmosphere in that era that the generalissimo- Alivardi Khan’s brother in law Mir Jafar Khan Bahadur- was himself not the most reliable of allies.

The anointed successor to Alivardi Khan was his grandson Mirza Mohammed, whom Alivardi Khan was fond of to a fault. Mirza ascended to the throne after the passing away of Alivardi Khan on 10th April 1756, at the young age of 23, assuming the imperial name of Siraj Ud Daula. Given the general atmosphere of intrigue in that age, where allies were not just useful but even indispensable for any ruler, it is hard to imagine a bigger misfit in the role of a ruler than Siraj. According to one contemporary source he

(made) no distinction between vice and virtue, and paying no regard to the nearest relations, he carried defilement wherever he went and… he made the houses of men and women of distinction the scenes of profligacy… he became detested… and people meeting him by chance used to say “God save us from him”

To add to his profligate, philandering ways, Siraj was also a man with a formidable temper given to using violent language- unbecoming of a man seated on the throne. Consequently, even people of high rank lived in constant fear of humiliation, possibly far worse consequences, depending on the caprices of the new nawab. The only exception was Mir Jafar, grand uncle of Siraj who was too senior to be cowed down by a 23 year old.

For his independence, Mir Jafar was relieved of his post soon after the ascension of Siraj. The new nawab stopped short of dismissing him altogether, allowing his grand uncle to retain the prestigious position of the paymaster to the army. Perhaps it was due to the fact that Mir Jafar’s support had been crucial in securing the ascension to the throne. The presence of an unreliable ally- one who now had reason to hate him too- in an important position was bound to end badly for Siraj.

Europeans in Bengal

There were three major European settlements in Bengal at the time- the British East India Company in Calcutta, the French company in Chandan Nagar (known at the time as Chandernagore) and the Dutch company in Chinsurah- all three of which enjoyed a flourishing trade.

All three companies had fortified their possessions with the consent of the earlier Nawab Alivardi Khan, who ensured that the fortifications did not go far enough for any of the companies to pose a threat to his own rule- a prudent policy, given what had just happened in the south. His attitude towards the Europeans is best summed by a contemporary

He used to compare the Europeans to a hive of bees, of whose honey you may reap the benefit, but… if you disturbed their hive they would sting you to death

The relationship between the nawab and the East India Company was subject to considerable friction at the best of times. Company officials complained that they were subject to frequent extortions by the nawab, who was denying them full enjoyment of the royal firman issued in 1717 by the Mughal emperor to whom the nawab owed suzerainty (its a different matter that the emperor’s writ had little force outside of Delhi by then). On his part the nawab maintained that the British were only entitled to privileges that were in the interests of the province and that they were abusing their privileges to the detriment of the government and the native traders.

What was actually transpiring is anybody’s guess- the two viewpoints are by no means contradictory. But what is beyond doubt is that both parties had reason to complain about the conduct of the other. The unpopularity of the new nawab further compounded things, as foreign merchants no did not feel anything approaching the fear that his grandfather evoked.

Matters were bound to come to a head.

A ‘Taxing’ Affair

Raja Ballabh, peshkar to the lately deceased diwan (the man responsible for tax collections), was called to render an account of his late boss’ transactions, to ascertain how far his estate was indebted to the nawab for the revenues of Dacca. Raja Ballabh was unable to give a satisfactory account, owing to which he was placed under strict surveillance virtually amounting to imprisonment.

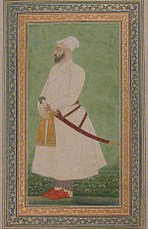

Alivardi Khan

At that stage Raja Ballabh sent his son Krishna Das with his family to Calcutta, with a letter recommending their admission to the British settlement. Why he did so is a matter of some debate. Some historians contend that Raja Ballabh did it to protect his family. The other possibility is that it was part of a conspiracy hatched in partnership with Siraj, to create a pretext for raiding the British settlement (there is circumstantial evidence supporting the later point of view). Given what had happened in south not so long ago, Siraj had either ample reason to suspect the British of skulduggery or wanted a pretext to raid their settlement depending on your viewpoint.

Trouble in Europe, Ripples in Bengal

Around the same time, the British and French were anticipating a fresh outbreak of hostilities in Europe (the seven years war would recommence a few months later). And so as the year 1756 arrived, the respective companies started fortifying their possessions, making no pretence of doing so, much to the consternation of the insecure Siraj, who sent messengers calling on both sides to demolish the newly laid fortifications.

The French tactfully handled the messenger, persuading Siraj that he had nothing to fear from them. The British failed to do likewise. No known copies of the reply from Roger Drake, the British governor at Calcutta, survive today. However, what is known beyond doubt is that Siraj’s reaction was hostile. Whether his rage was spontaneous or pre-planned is anybody’s guess, but what followed was utterly predictable. The nawab’s forces raided and shut down the British factory at Kasim Bazar (or Cossimbazar) and turned towards Calcutta.

The Nawab’s forces surrounded the British possession on 20th June. With hardly any troops at his disposal, Governor Drake hastily evacuated the fort, leaving the survivors to their own devices.

Siraj Ud Daula

The Black Hole

The nawab’s soldiers plundered the British settlement, but no bodily harm was done to any of the people living there, nor was there ill treatment of any kind. It looked like the siege would pass of relatively calmly until a group of drunk British soldiers assaulted some of the Nawab’s soldiers.

The assaulted soldiers, who were evidently under orders to restrain themselves, complained to the nawab. The enraged Siraj asked ordered the offending troops to be confined in the black hole- a dark, dingy room without ventilation, which was used for confinement of errant soldiers. The overzealous soldiers unwisely confined all the prisoners (numbering, it is said, over 100), irrespective of their background- in a cell meant for a handful of people.

The combination of the incredibly congested room and the fact that it was the hottest period of the year, was bound to be lethal. Unfortunately, none of the prisoners could be released without the consent of the nawab and given his temper, no one dared disturb Siraj in his sleep. The confinement lasted overnight.

When the confined prisoners were finally released on the morning of 21st June 1756, only a handful of them were still alive. In the words of a survivor

…when only twenty-three of one hundred and forty-six who went in came out alive, the ghastlyest forms…were ever seen alive, from this infernal scene of horror.

If plunder was the chief motivation behind the sack of Calcutta- as some historians have insinuated- Siraj must have been disappointed to recover a relatively paltry fifty thousand rupees and not the lakhs of rupees he might have expected. Nevertheless, he had successfully asserted his authority over the upstart British.

He would pay dearly for it.

Sources

- Ghulam Husain Salim, Riyaz us Salatin (Translated by Maulavi Abdus Salam), The Asiatic Society, Calcutta (1902)

- S.C. Hill, Bengal in 1756-57, John Murray, London (1905)