Tags

this is the second installment of the three part series on the reforms of 1991

An Economic Crisis

As he stood on the cusp of becoming the most accidental of Prime Ministers, veteran politician PV Narasimha Rao was confronted by perhaps the worst economic crisis since independence. India had just enough foreign exchange reserves to buy oil for two weeks. Rating agencies had already downgraded India, which was on the verge of a sovereign default. Economic reforms, pending since several months due to political instability, could no longer be delayed.

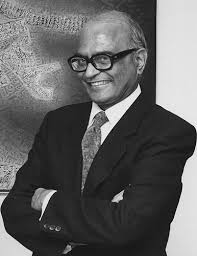

Narasimha Rao knew that he needed above all a capable finance minister, ideally a non-political one, who would not be constrained by ideology. He plumped for Indraprasad Gordhanbhai Patel or IG Patel, as he was commonly known. The former governor of the Reserve Bank of India (RBI) and lately director of the London School of Economics, Patel was the ideal man for the job. Unfortunately for Rao, the self-effacing Patel politely declined the offer.

With Patel out of the race, the second choice Prime Minister turned to his second choice finance minister- another former RBI governor, who had been the advisor on economic affairs to two former Prime Ministers and was serving out the rest of his distinguished career as chairman of the University Grants Commission (UGC). Dr. Manmohan Singh had the dual advantage of being a non-political figure as well as being a world renowned economist. He was the perfect frontman, who could be feted or dumped, depending on how things turned out.

IG Patel (1924-2005)

Joining the Pieces

As the cabinet of ministers took the oath on 21st June 1991, Rao surprised everyone by inducting into his cabinet Dr. Manmohan Singh, a man little known outside of academic or official circles. The following day, he was named the finance minister. The first piece in the puzzle was in place.

The second piece in the puzzle was the drafting of a new industrial policy to free up the economy, which had been shackled under a plethora of draconian restrictions since the 70s. The new industrial policy had been in process since the 80s. To complete the unfinished work Rao chose Amarnath Verma, who had co-authored the draft industrial policy earlier, as his Principal secretary. Supporting Verma was a young economist called Jairam Ramesh, who was inducted as officer on special duty in the Prime Minister’s office (he would be transferred to the finance ministry later that year).

Having taken care of the technical aspects, Rao turned his attention to the political aspect of the challenge. He was shrewd enough to realise that the proposed reforms would run into opposition from within the Congress party, particularly the old guard which would be averse to a departure from the economic vision of Nehru and Indira Gandhi. To overcome that challenge, he handpicked the 45 year old P Chidambaram, a Rajiv Gandhi protégé. A brilliant lawyer, Chidambaram was the ideal troubleshooter.

The team in place, Rao embarked on a bold journey.

The PM and his Finance Minister

Declaration of Intent

On 22nd June, barely twenty-four hours after he was sworn in, Prime Minister made his first address to the nation. Acknowledging the economic crisis, he famously said

We are committed to removing the cobwebs that come in the way of rapid industrialisation

Not many took him seriously. Rajiv Gandhi, who had a much stronger mandate and was the undisputed leader of the party, had been thwarted in his attempts to usher in economic reforms in the mid 80s. There was no reason to believe that Rao, who had not even been his party’s first choice for the prime ministerial seat and was heading a government that did not have a clear majority, would be able to succeed where Rajiv Gandhi had failed. In fact, Rao was largely seen a man doing a holding job. The New York Times reported that

Mr. Rao is widely viewed as a transition leader…whose selection was intended to calm the factional divisions in the Congress Party as well as the nation.

Besides, Narasimha Rao was not known to be a particularly decisive man. In fact his indecisiveness made him the butt of several jokes at the time. The general mood at the time was best summed by the then editor of India Today Aroon Purie, who wrote (on Narasimha Rao’s newly inducted cabinet of ministers)

It was expected…that as a prime minister, Rao would opt for the safest and most familiar names. He did just that.

PV Narasimha Rao would soon make them eat their words

Hop, Skip and Jump

The Indian Rupee back then was pegged to a basket of four currencies: the Pound Sterling, the US Dollar, the Deutsche Mark and the Japanese Yen. As of 30th June 1991, the Indian Rupee traded at Rs. 21.14/ $. Pretty much every expert on the matter concurred that the currency was significantly overvalued, which made Indian exports more expensive and consequently, noncompetitive. With a crippling balance of payments crisis, devaluing the currency to reflect its correct value was the most logical thing to do.

Unfortunately, currency devaluation was (and still remains to some extent) a politically sensitive matter. Indira Gandhi had paid dearly for devaluing the currency in 1966 in the face of another economic crisis (more on that some other day), an episode that was relatively fresh in popular memory. The fallout of a devaluation could be huge, more so given the fact that the government was dependent on outside support from the communists for its survival.

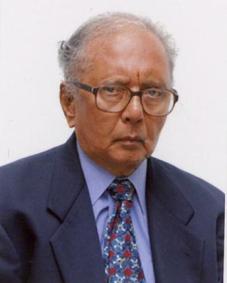

S. Venkitaraman

With the humiliation of a sovereign default looming, Rao decided to take the plunge. The project, code named “Hop, Skip and Jump” was approved by the Cabinet Committee on Political Affairs, following which S. Venkitaraman, the then Governor of the Reserve Bank of India, was notified.

With a view to containing the political fallout, it was decided to devalue the currency in two steps. On Monday, 1st July 1991, the spot selling rate of the US Dollar was revised from Rs 21.14/ US$ to Rs. 23.04/ US$. The Finance Minister Dr. Manmohan Singh, who had been the main proponent of the two-stage devaluation, described it as a routine adjustment. Denying that the move was undertaken under pressure from the International Monetary Fund (IMF), he said

We will not do anything under pressure and which is not consistent with our national interest

Industry body Confederation of Engineering Industries (which changed its name to Confederation of Indian Industries- CII- in 1992) welcomed the move. The following day, Commerce Minister P Chidambaram, Rao’s troubleshooter, held a meeting with media representatives to explain the logic behind the move and prepare them for major structural reforms which were to follow shortly.

The following morning- Wednesday, 3rd July 1991- the Rupee was further devalued to Rs. 25.95/ US$. In the short space of two days, the currency had been devalued by a staggering 23%. To contain the inevitable political fallout, Dr. Manmohan Singh officially announced that there would be no further devaluation.

Prime Minister Rao, with a view to building up popular support for the move decided to tell the people of the country as it was. In a televised address on Doordarshan- the official government channel and the only television channel in India in that era- he famously said

…this is only the beginning. A further set of far reaching changes and reforms is on the way…

Follow Up

The following day, Commerce Minister P Chidambaram delivered on his promise made on the 2nd by unveiling a series of trade policy changes, virtually amounting to a completely new trade policy regime.

In the meanwhile, Finance Minister Dr. Manmohan Singh was furiously working behind the scenes to avert the looming sovereign default. In a replay of what had happened a few weeks earlier, Air India transported 25 tonnes of gold to London on 6th July, followed by 9.8 tonnes on the 13th and a further 12 tonnes on 18th July. Against the gold shipments, the Government of India obtained financial support to the tune of $ 400 million, which staved off the looming default by a few days.

By mid July, Rao and his team had successfully managed to postpone the looming crisis. However, structural reforms- the only long term solution- were still pending. Consensus for structural changes were still needed from within the party, let alone the wider public.

A humongous challenge lay ahead.

Sources

- Shankar Aiyar, P V Narasimha Rao: Accidental PM and Accidental Reforms, New Indian Express, 19th June 2016

- A.K. Bhattacharya, Two Months That Changed India, Business Standard, 2nd July 2011

- P.R. Ramesh, PV Narasimha Rao: The Outsider Who Dared, Open Magazine, 4th March 2016

- Swaminathan S. Anklesaria Aiyar, Unsung Hero of the India Story, Economic Times, 26th June 2011

- Shaji Vikraman, On this day 25 years ago, an invaluable devaluation, Indian Express, (Updated) 6th July 2016

- Ira Dugal, India’s tryst with currency devaluation, Livemint, 2nd July 2016

- July 1991—the month that changed India, Livemint, 1st July 2016

- Bernard Weinraub, Man in the News, New York Times, 22nd June 1991